© WIRE Magazine, UK

Issue #340, June 2012HERE COMES THE FLOOD

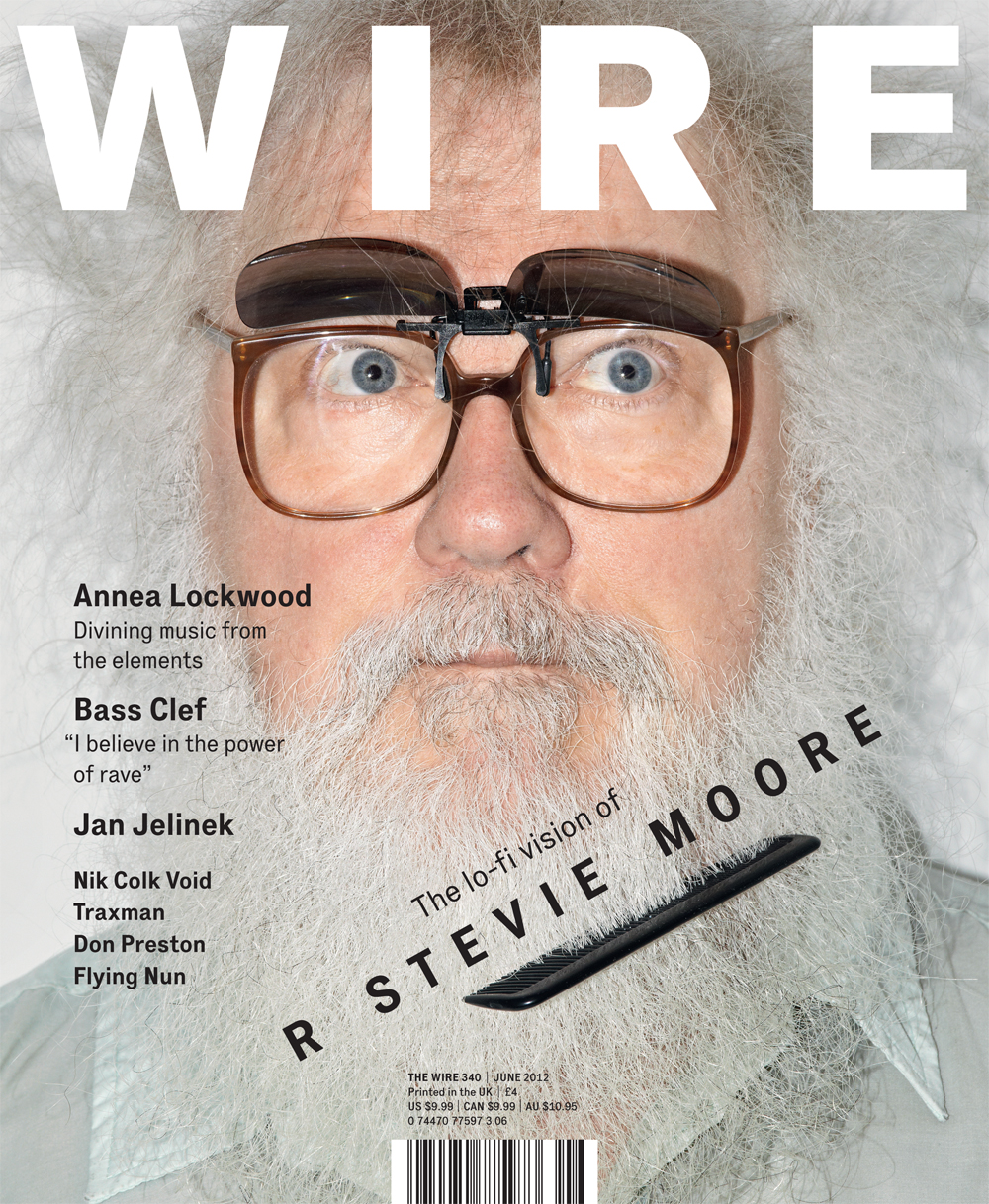

The lo-fi vision of R STEVIE MOORE

The wandering minstrel of

American outsider music

anticipated lo-fi, DIY,

Hypnagogic Pop and more

with his unvarnished debut

Phonography in 1976.

Since then he has poured

out a deluge of more than

400 records, spilling into

power pop, Minimal Wave

electronics and primitive

hiphop, and he's now

revered by everyone from

The Residents to Ariel Pink.

By Matthew Ingram.

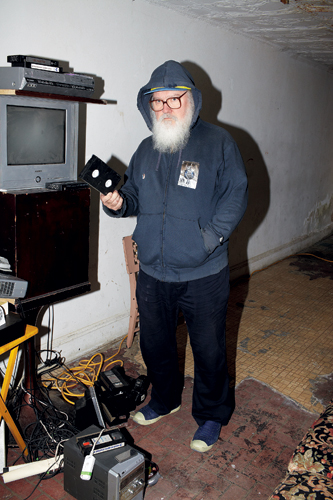

Photography by Michael

Schmelling, Brooklyn New

York City, 14 April 2012

In late February 1978, Robert Steven Moore, aged 26, set out northwards from Nashville, Tennessee. He had next to no money. It was cold and the highway was dangerous in places. Packed with his few possessions but not his records, he was unsure whether his Austin Marina would manage the trip. It took him two days to make the trip to Montclair, New Jersey. Two days later he secured a job in a record store. “I was frankly scared to death, all alone,” he says now. “In retrospect, it was quite a risky jump headfirst into the deep end, quite opposite from my usual hesitancy to brave such life-changing challenges.”R. Stevie Moore is one of America’s truly iconoclastic modern musicians. Moore might not have been the first rock musician to go entirely solo, recording every part from drums to guitar, but his earliest works were at least contemporaneous with other one-man band works like Alexander ‘Skip’ Spence’s Oar (1968), Paul McCartney’s McCartney (1970), Todd Rundgren’s Something/Anything? (1972) and Roy Wood’s Boulders (1973). However, he was the first to explicitly aestheticize the home recording process itself. Questioning the culture industry’s validation of high fidelity, Moore’s recordings celebrated the unburnished, the intimate, the vulnerable and the deranged, making him the great-grandfather of lo-fi. His echoes can be heard in the music of artists like Pavement, Smog, Guided By Voices and Beck, and through his disciple Ariel Pink, he has unwittingly provided the template for the entire movement currently known as Hypnagogic Pop.

However, Moore’s vast body of work can’t be reduced to mere formal invention. Over an untold number of LPs, in the language of power pop and AM rock, he has crafted an extraordinary quantity of luminous songs. In the same way Scott Walker’s songbook revealed vertiginous depths in cabaret and lounge balladry, they express emotions unfathomed elsewhere in their respective genres. Moore has also turned out a range of generic excursions that would surprise the most adventurous listeners. This raw energy is what keeps him, now in his sixties, as busy as ever. He starts a European tour this summer, following an LP collaboration with Ariel Pink. Just when life couldn’t be better, in a typical act of self-sabotage, he carelessly titled the album Ku Klux Glam.

The trip to New York in 1978 had been a long time coming. “I did want to get out of Nashville,” Moore recalls in his gently Southern twang, talking from his Nashville home. “But how convenient it was that I knew something was happening big time! Not only the popular punk rock/new wave stuff that was exploding, but also the essence of DIY was right there. It was a curse to be signed by a major label at that stage, and that was why the uproar of indie labels and punk rock, ‘make your stuff at home’, it was perfect for me. The ultimate thing was that I did have one connection with New York: my Uncle Harry.”Moore’s uncle, Harry Palmer, used to play in obscure, Boston based progressive rock group Ford Theatre; he also laid claim to discovering outsider music legends The Shaggs. Palmer had become a tireless supporter of his stubborn nephew, putting out Moore’s legendary Phonography (1976), a compilation of home recordings, on his own HP Music label. “My Uncle Harry almost used to come to tears on our many long phone conversations about ‘You’ve got to get a band together’. He would even say, ‘I know some people with a creative production company or label here in New York City’, and – as my recordings got better and more presentable – he was always saying ‘I would be glad to put together a little package, but it’s worthless if you don’t have some kind of a following, even a tiny following. You have got to go out and make a name for yourself on stage.’”

Clearly, without Palmer’s nurturing presence, Moore might never have escaped his own background, let alone set off to make a new life in New York. “I often don’t talk about him enough,” he now admits, “about how important he was to keeping me on track. He, too, was extremely frustrated with my bad luck in getting people interested and getting acknowledged, but the fact that he had to deal with crazy old me. Not that I have this horrible abusive personality or anything, or was difficult to deal with, but just the fact that I was so set in my ways of being stubborn.

The influence of this caring uncle gains a whole other level of gravitas when understood against Moore’s immediate family background. His father is the celebrated Country session musician Bob Moore, member of the Nashville A-team. Not to be confused with Scotty Moore, Bob played bass for Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis and Bob Dylan, as well as the likes of Sammy Davis Jr, Julie Andrews and Burl Ives. In 1994, Life magazine named him All-Time Greatest Country Music Bassist. Moore Senior was a deeply troubled individual. “He made it big, and he didn’t have a very good childhood at all,” says Moore. “He starved. And hated his father. It was a standard thing that whatever I saw I didn’t like as far as being brought up. And neither did my sister and brother. Nor my mother. It was a very intense, dramatic, abusive childhood, with all this money coming in, because he’s doing these amazing historical sessions. It’s very, very sad. He was very disappointed in me because I was not a get-up-and-go type. He wanted to put me through college. For me to take charge, and I never did take charge. I was very inhibited and introverted.”

In grotesquely ironic circumstances, aged eight, the young Moore was roped into the sessions for Jim Reeves’ saccharine “But You Love Me Daddy”, providing the angelic foil to the narrator as he castigates his young son:

Reeves: “Your five year old face is a dirty disgrace”

Moore: “But you love me, Daddy”

Reeves: “You scatter your toys and you make too much noise”

Moore: “But you love me, Daddy”

Reeves: “You know, little lad, you can be pretty bad”

Moore: “But you love me, Daddy”

Reeves: “You wake me at dawn when I want to sleep on”

Moore: “But you love me, Daddy”

Recorded in 1959, the song slept for a decade before becoming a Top 20 hit in the UK. “It’s alarming in its irony,” remarks Moore, “but I never really thought about it much. I’m used to the fact that I never had my father as a support when I needed him more than ever. Because he was wrapped up professionally. Yeah, and because he had issues too. He was a terrible father.” The course of his musical life can be viewed as a mirror image of his father’s. Any other son in such a position, especially one so naturally gifted, might have been expected to follow in his father’s footsteps. Indeed, he did spend some time doing session work, but was completely indifferent to it. He would race home after each date and plug in to his reel-to-reel tape recorder – the future grandfather of DIY home recording’s first set-up?“I was a kid,” he says. “Why would anyone think I was setting out to change the world? I wasn’t making a statement; it was just convenience. That’s what DIY is: it’s convenience and cheapness and freedom. You’re able to do whatever you want, and you can hold it back from the listeners if you want – but of course for me it was the complete opposite. I was not setting out to make any kind of statement. That’s the beauty of the story. They call it innocence, and that’s always what I’ve been. Having to deal with the negative aspect – the struggle for acceptance and acknowledgement – that just poured fuel on the fire. How awful it would have been in 1973 or 1974: ‘Guess who called? Todd Rundgren, and he knows somebody and he wants to get an album together: I would have loved that. I would have jumped immediately for that kind of opportunity, but it never came.”

Though Moore has become so indelibly associated with lo-fi (as an aesthetic choice), he claims to have no attachment to poor recording. Indeed, the clarity and depth of his recordings are remarkable, given the process he used throughout the 1970s of bouncing tracks in sequence (first drums, then guitar, bass and vocals) onto a reel-to-reel. The same goes for his mind-bogglingly sophisticated arrangements. Yet he has worked in professional studios, notably on his albums Clack! (1980), Glad Music (1986) and Teenage Spectacular (1987). “Going into a studio did not mean that it was better,” he cautions. “Sure, it’s much bigger and better in some ways – it’s not even that expensive, you just pay the hourly rate. Sometimes I’m not quite as comfortable, but that goes hand in hand with the experience. There’s a lot of forcedness in the studio. People watching the clock. Me watching the clock! You can’t compare it with the freedom of being at home. There are a lot of hardcore aficionados who always prefer the original home demos of songs that I went in and tried to remake.”

Moore might well hold all his work in equal esteem (home recording and the studio as merely different sides of the same coin) , but one senses he has an almost scatological urge to be ‘a dirty disgrace’, to revel in the ‘unprofessional’ dimension of home recording. Received wisdom also has it that he needs an editor, a censor of sorts. He doesn’t refute the charge – he’s more than open to people editing his output. With good reason: it is rumoured that Moore has released close to 400 albums, though even he is unsure of the exact number. “No actual proven number, no,” he sighs. “It remains very vague and virtually impossible to verify. On close inspection, 400 might seem stretching it a bit, and yet when it comes down to every bit of home taping I’ve ever done, including producing friends, alternate dub versions, session discs, audio verite ephemera, etcetera, it suddenly becomes an unlimited guess.”In this torrent of releases, he casually splices the divine with the diabolic. Phonography, for instance, features both the moving ragtime stride of “Goodbye Piano” and a diatribe, “Explanation Of Artist”, delivered over the sound of him urinating.

However, when it comes to his would-be editors, it is clear which strand of Moore’s work is preferred. Many of his most critically successful releases have been compilations centred on his exquisitely arranged, lavishly melodic, guitar based compositions. Phonography (1976), Delicate Tension (1978), What’s The Point?!! (1984), Greatesttits (1990), Hobbies Galore (2003) and Ariel Pink’s Picks (2011) are all compilations of peak period Moore: his purple patch of 1970s and 80s material, dominated by his twisted vision of classic AM rock. One of the abiding mysteries surrounding him is how he managed to fall into the freaky enclave in which he resides. Like the apochryphal Chillwave artist whose music sounds like Hall & Oates recorded on a Tascam Portastudio, Moore’s songs – check tracks like “Part Of The Problem”, “Cool Daddio”, “Colliding Circles” – often contain a glaring commercial kernel. Their loose, fresh quality appeals to the fans of the ramshackle ‘underground’ recordings of Meat Puppets or Big Star, but Moore’s material also has the kind of ‘finished’ quality that The Beach Boys were regularly sending into the charts.

So why has Moore found himself feted by such uncompromising iconoclasts as The Residents, Chris Cutler and Ariel Pink? Why is he in the ‘weird’ camp at all? “Me and [Moore affiliate] Irwin Chusid always had the dilemma that he did not want to present me as an outsider,” he says, “like a Wesley Willis or a Daniel Johnston, or these people that are touched in the head and have a certain gift. I love outsider music, but they don’t have the [particular] talent I had. I love these guys, but they have no concept as to how to write or arrange a Brian Wilson song.True rock of the kind Moore has plied over the years represents a spirit very close to the original rupture of rock ‘n’ roll around 1956. “I’m almost a little too young to really fully appreciate the 50s stuff,” he agrees. “I loved it. That was my childhood. Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Little Richard, Carl Perkins, all of it, all the rockabilly. Loved it as a child. But that’s interesting how that rock ‘n’ roll applied to DIY, because that’s what they were doing, too. Not to mention their own independent labels. They didn’t need corporations. They sold records out of the trunks of their cars. Even The Beatles had to put on suits for Brian Epstein. But when you think about Elvis and Sun, that’s somebody doing it DIY to the maximum.”

Yet as soon as you start to recast Moore as a subversive AM rocker, you remember his extensive catalogue of exploratory music – and you’re back at square one. There are countless variations of R. Stevie Moore to choose from. Naturally, there’s the preponderance of his brand of Nashville concrete and experimental synth work, but much else besides. “Horizontal Hideaway”, from Games And Groceries (1978), is an immaculate slice of proto-rap, uncannily predating even the release of 1979’s “Rapper’s Delight”. The title track of Dumb Philosophy (1981) features a radio evangelist ranting over an astringent rhythm track which apes Byrne & Eno’s My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts; Column 88 (1981) is full of the influence of PiL and Killing Joke. On Musts (1983), Moore indulges in lounge jazz versions of his greatest hits, minimal synth skits, radio theatre and experiments in mobile recording. Come Persevere (1991), he’s toying with hiphop on “Oil”, glitch avant la letter on “Skip Digitals”, and even Techno on the memorable “I Got The Fax”. On Conscientious Objector (2004), we get drum ‘n’ bass on “Yung & Moore Show” and Metal on “Subjectivity”.

Radio is a recurring motif, in the form of phone-ins, recordings off the airwaves and even hilarious jingles. Moore links his leftfield inclinations with what he describes as a radio show aesthetic. “When I was young, you were able to hear more diverse radio programming,” he remembers. “Then in the 80s and 90s it became ‘just forget it’. Except for WFMU. I was there [at WFMU] when I first moved to New Jersey in 1978, and then I was on the staff and had a weekly show for four or five years. Then I did fill-ins and kind of drifted away from it. But that’s still going strong. It’s not quite as freeform as it used to be, which I regret. It’s like slot programming. Everybody’s hour sort of stays the same style, which removes the freeform thing for me. But again, this is something that has been both a blessing and a curse for me, but this is just who I am and the kind of artist I want to be.”

Sometimes this variety can be grating. Moore uses the buzzword diversity to describe his magpie tendencies, but often one senses he’s reluctant to knuckle down and quit larking around. “Sometimes, either accidentally or on purpose, I have lost the talent to sit and arrange good, solid, brilliant pop,” he says. “Back then it came natural, without even thinking about it. All of those great favourites like “Part Of The Problem” and “Play Myself Some Music” – 70s and 80s stuff – I don’t discipline myself to sit down and think, I have to write myself some songs. I don’t like to do that much anymore; I’d rather sound-paint and mix and all the things besides, because I’ve done it for so long. But of course when I do write songs, it’s like heaven. That inspiration comes back out of my head. Into my fingers. And I start to play. I’ve always been like that.

“My latest album, Advanced, is a pure power-pop songwriting studio record,” he continues. “My friend for all my life, Roger Ferguson, helped me put that together in his home studio. And he was, like, disciplined with me, which I loved but was kind of strange, and we both laughed about it. Because he knows me so well, that I needed to be reigned in every once in a while. He laughed about it but somehow I felt smothered, because it was like 12 or 14 tracks of song-song-song. Everything very straightforward.” It’s a shame, because on the evidence of the album, Moore does indeed feel constrained. Perhaps inevitably it lacks the magic of his earlier material.

This artificial divide between his ‘avant garde’, ‘free’ music and his songwriting is threatened by a new aleatory method of competition he has developed. “A lot of my recent songwriting,” he explains, “I’ve been having a blast with a method called ‘blank sheet of paper’. If I want to write a great new song with totally original chord changes and melodies, I get a black sheet of paper and start writing chord letters. I don’t hold an instrument. I don’t sing a melody. I do it almost like a mathematical exercise. I write all these chord letters, and the song starts to write itself. It’s almost scientific. I love that. You don’t know what chords sound like until you start putting melodies on top of them, and harmonies, and a different bass note to the A chord. I’m an arranger, that’s how I’ve always understood that stuff. I can even play this game with rules. Because what happens when the song starts to write itself, you feel the temptation to change it and to improve it, and if I wish I can make a rule and say, no, that’s not allowed, the song has to stay just as it was in the beginning.”

Though he refutes the notion point blank, you sense that without the usual supporting network of label, manager and group, Moore occasionally gets lost and ends up pandering to his weaknesses. For example, the material of his post-punk era, bookmarked by Clack! (1980) and Crises (1983), is strong and lovingly put together, but it’s difficult to reconcile his essentially ebullient persona with the alienated material. He started slipping back into the stream with “Time Stands Still”, from It’s What’s Happening Baby (1983), which was in tune with the stirrings of nascent 1960s revivalists REM and The Dream Syndicate. Inevitably, Moore has fielded a constant barrage of opinionated sniping over the years. Everybody, it seems, wants to tell R Stevie Moore what to do with his life.Nevertheless, he is happy to acknowledge the steering influence of a few guiding voices. These include his Uncle Harry Palmer and the songwriter Victor Lovera, with whom he founded the shortlived group Herald Goods, but also Irwin Chusid. A champion of outsider music (he coined the term in Songs In The Key Of Z, published in 2000) and a WFMU stalwart, Chusid is notable for his work on The Langley Schools Music Project, and the back catalogue of Juan Garcia Esquivel and Raymond Scott. He has drummed for Moore, on and off, since the early 1980s, and compiled What’s The Point?!!. Also important is former Charlatans singer Tim Burgess, who last year released a Moore single on his O Genesis label. But these days Moore is most associated with Ariel Pink. “We’ve only known each other for 11 or 12 years now,” he says. “He came through the internet, through email, and sent me cassettes and CD-Rs, and I opened up to him very much. I almost always opened up to people who came to me like that. And believe me, ever since Ariel there’s a million sound-alikes. Suddenly everybody knows my name because he’s been namedropping me, and you can’t buy that sort of exposure. It’s amazing. Now we’re trying to work together – it’s a dream come true. We almost got together as a double bill travelling Australia and the Far East, but it didn’t happen.”

Fruit of the Pink/Moore alliance came this year with the excellent album Ku Klux Glam. Moore gently acknowledges that, despite the strength of recent albums like Far Out (2004), his muse has become recalcitrant over time, saying, “My back catalogue is really what I am rather than a song I just wrote or a new record I’ve got coming out.” And Ku Klux Glam is an extraordinarily impressive release for a 60 year old. The bonkers “Dutch Me” and “SteviePink Javascript”, in particular, rank among his best work.

For more than just creative reasons, not having a group was an issue for years. “That used to be a major, major drawback for me getting anybody’s attention,” he laments. “I didn’t sit in my bedroom recording because I thought it was going to be a popular hobby decades later when everyone didn’t need to go outside. I do have issues with being in public. Not agoraphobic, I’m not that bad; rather I have a fear of walking out in public. But I was never a big salesman and I was never big on hanging with buddies who made music together. I dabbled in it, but when I saw how great it was to just be home alone under headphones, I was just non-stop – I could not control myself. But back then, in Nashville, there were no places to play even if I had had a great glam rock sounding band.

“Me and my best friend of that time – a huge influence on me – Victor Lovera, when we met in ’71, he had the songwriting and singing thing down great, he was very individualistic. When he met me, I was the thinker and the electric guy, but not much of a performer. I didn’t really write, I didn’t really sing very well, but we got together and heavily influenced each other. The big thing at the time was Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust and you gotta know that we were fantasizing about, ‘Man, if we could only get a bass player and a drummer’, and we dabbled in that, but it was pretty hopeless trying to do that in Nashville. There was no place to play and get everything together, so we could get the hell out of Nashville and start playing properly. Where? Atlanta? Everybody wants to go to Chicago, to Detroit, to New York. We were stuck. I was stuck here, and the only thing working for me was home recording. Back then, all I would have needed was a little video clip of me on stage and an audience going crazy, even if we had to rig it up and make a fake. I couldn’t just snap my finger and put a band together, because I was a one-man band too. But under that I did have my underlying laziness. I didn’t want to make that happen, because I knew it wouldn’t work in Nashville.

“I haven’t been much of a band guy until just recently,” he continues, “but now I’m really loving it, and my guy in New York, JR Thomason – he’s from Texas, young, in his mid-twenties, lives in New York – he’s my main guitar player in my new band, and when I feel like I’ve lost my way, perhaps he can help with that.” Sometimes he clearly does need help. He remarks touchingly: “There’s a lot of teenage naivety with me too. I know nothing about finance, I’m in big trouble as far as being a responsible adult. I’m a basket case by now. In some ways I’m regretful. I’m proud of it because I’m stubborn and, as you say, it’s a little too late to turn back now and change things.”

Tied up with this social awkwardness has been his difficulty in love. Relationships with women, a recurrent theme in his music, have given him as much material as problems: “It’s been a rocky road. It’s worse than ever, but I’m getting too old to keep crying my eyes out over it. It’s a joke. I mean, I have had great relationships. I’ve had durable relationships and I’ve also had the opposite. I’ve also had the risk of being a loner and isolated and wanting to be by myself, which goes totally against the grain of making a relationship last. I’ve never had interest in marriage or raising a family, but I’m extremely romantic. But getting on in years, so that’s the big joke these days. The running joke is to find these girls and say, ‘Hey, how do I get in touch with your Mammy?’ And this [holding up big white beard] doesn’t help. But people don’t say to Robert Wyatt, ‘Hey, Santa Claus!’ I’m going through that constantly. I just roll with it. The romantic thing goes very deep. I’ve got a huge heart – I have victories and I have failures.”

"It

is

a

sad

story,

a

struggle

without

payback.

My

whole

life

has

been

the

underdog

struggle.”

A second abiding theme in Moore’s music has been a hankering for fame. Not an album goes by without him thanking a baying (canned) audience for their support; nor without tracks like his cover of Dr Hook’s wishful “Cover Of Rollin’ Stone” from Teenage Spectacular, or the ambitious “Bigger Than The Beatles” from 1984U (1984); nor without Moore’s maudlin reflections like “Why Can’t I Write A Hit?” or (facing ignominy) “I Will Want To Die”. “I carry that back to my childhood, I guess. Seeking acknowledgement. In a lot of ways, I’m an actor in a film of my life, so sometimes I’ll exaggerate my devastation at not achieving the fame – and it makes for good poetry. I wish I wasn’t so desperate, and yet I’m damn glad I’m so desperate because it kept me innocent and not a bullshit artist – I’m constantly scratching my head saying, did I do well? It’s basic fun, but it’s also agonizing because it is a sad story, a struggle without payback. My whole life has been the underdog struggle.”

Experiencing his father’s semi-celebrity first hand as a child must have underlined his indelible association between fame and love; cementing the idea of fame as a panacea. “It wasn’t like Hollywood and garish money and celebrities,” he says. “It was a Nashville experience. I got to see [it all close-up], and I wasn’t a big Country fan, but I was damned proud of my father and I loved the process of watching them put together Patsy Cline hits. I was eight or nine years old, keeping my mouth totally quiet in the studio watching this history being made, and it was fantastic quality. I was very shy and introverted and I would be with my father in the studio, and I would just be quiet. I had no personality, except I behaved myself. Very polite, but I had nothing to add to any of it. And I wasn’t able to impress anyone as a person.”

Unconventional Tennesseans have often struggled with the almost oppressive weight of the tradition of the Grand Ole Opry, and I see Moore in kinship with local eccentrics like Mickey Newberry as well as Southerners who twisted the gutbucket mode of Country into new shapes: Willis Alan Ramsey, Mike Nesmith, Gene Clark and John Hartford. Now he freely namechecks Hank Williams and George Jones, but many years passed before Moore could appreciate his own musical legacy and the music of his father. Indeed, he says, it didn’t happen until he was firmly ensconced in New York. “I needed a new genre to get into with record collecting. I had every British 60s Invasion band, A to Z. I had everything. I had hard rock. I had experimental electronic music growing up. I loved all kinds of stuff. Comedy records and even bizarre sacred gospel records, but I didn’t go deep with Country. But then in the 80s a light bulb went off in my head, and I started hearing all these British import records of hillbilly music. I’m not talking standard Country, I had a lot of Country growing up with my Dad and major label stuff, but for me it was the twangy hillbilly stuff that was driving me nuts, so I had to collect it all. It’s interesting how record collecting can do that to you.“And the same with blues,” he continues. “When I was trying to make it in Nashville in the 70s, there was no rock happening in Nashville except The Allman Brothers, and I hated that stuff. Southern rock. Everything was boogie. I was a Beatles guy. I wanted verse-verse-chorus, brilliant chord progressions, 4/4 Kinks, hard beats. I didn’t want [spits] boogie. So I really hated blues and didn’t have much of it at all. Everybody knew about BB King and people like that, but I just wasn’t interested. The same thing happened in the 80s as what I was saying about Country. I couldn’t stop getting John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters and Robert Johnson [records]. That was like the new punk rock to me. That’s the real deal. Not like Allman Brothers boogie.”

About 18 months ago, following a failed relationship Moore returned from New Jersey to Nashville. But he was turned onto Country via British releases of hillbilly music. He’s an avowed Anglophile, his catalogue sprinkled with skits like “Welcome To London” (on Stevie Moore Or Less, 1975) and tracks like “London’s Not Home” (on Pop Pain, 1981). “I love Peter Sellers and The Goons and Monty Python. You have no idea how it’s been over here: the intense inspiration. I don’t want to rank The Kinks over Bill Haley And The Comets. America has amazing stuff as well, but I’ve always been big on the British thing. It is The Beatles, because Cliff Richard never did anything for me. Irwin Chusid coined the term that my music was like [The Kinks’] Muswell Hillbillies in reverse.”Remarkably, he made his first visit to the United Kingdom last year. “I came to the UK right when the riots were happening. We even had to cancel the Manchester show because the club was in a bad neighbourhood, the night after the fires and all that stuff. We played Birmingham and London and Newcastle, Bournemouth. We were driving along the M4 and there’s signs for the ramp to Swindon, and of course that’s where my XTC mates are. We had to pass the ramp, we were on our way to Cardiff.”

Right now, things couldn’t be better for Moore. He has the perfect distribution outlet in his Bandcamp page, where you can find his greatest albums (see accompanying sidebar). He has a great new album with Ariel Pink and, at last, he has a group. After all these years, something like fame has arrived. The phone is ringing off the hook: “Things are just exploding left and right and I can’t keep up with it all. I need management. It’s a great problem to have, but I can’t take advantage of it. I’m just one person. It’s crazy.”Up until 1993, when he switched to recordable CDs, Moore was indelibly associated with tapes, releasing the, on his label RSMCC (R Stevie Moore Cassette Club). So it makes sense that this flurry of interest is occurring in the wake of a tape revival. “I’m mildly amused, which means I care because I pay attention to it,” he smiles. “I’d have to get a player because I don’t even have one at the moment. I agree that they’re quaint and they’re charming and they have that great feel. When I was back in the cassette revolution there was nothing better, because I could make my own record at home. You pop the tabs out so it can’t get erased – that is all fantastic, but to see these kids that are 20, 30 younger than me celebrate them – I just laugh. Because for me it’s still CD-Rs. I love vinyl, because vinyl is huge, but of course no one could press their own vinyl in their living room, and I also have mixed feelings about the digital age. It used to bother me about MP3s, but now I’m loving it. That reminds me about Facebook, too. I tell people, I’m a motherfucker on Facebook, because I use it like it’s performance art and I get on there and even my own friends will say, ‘Why do you post so much?’ and I’ll say, ‘There’s the exit door!’”

Where have we heard that before?

“Yeah, like, ‘Why do you have 400 albums?’” ❑~

R Stevie Moore plays at Field Day, London on 2 June: see Out There. Ku Klux Glam is out now on RSMCC. rsteviemoore.bandcamp.com

|

R Stevie Moore on record Matthew Ingram picks six essentials

Phonography

Swing And A Miss

Delicate Tension

What's The Point?!!

Glad Music

Ariel Pink's Picks

|

PRINT ARTICLES

PRESS-KIT

r. stevie moore in

A prophet is never appreciated in his own land and time.

HOME | NEWS | DISCOGRAPHY | ALBUMS |

TAPOGRAPHY

| LIVE | ARTICLES |

LYRICS | PHOTOS | AUDIO | VIDEO | YOUTH | FUTURE | FATHER | LINKS | SEARCH | CONTACT

"Is sloppiness in speech caused by ignorance or apathy? I don't know and I don't care." - William Safire. American journalist and speechwriter. (1929 - )